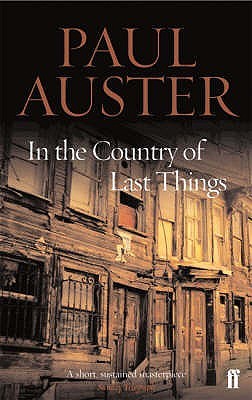

I’m a fan of utopian and dystopian literature, so when Paul Auster’s 1987 novel In the Country of Last Things was recommended to me, I dropped what I was reading at that time and set to it immediately. I was drawn into Auster’s imagery right away from the beginning; in fact, many of his descriptive passages were quite harrowing, setting the scene of this futuristic no-named city well, but I found that the more I read, the more the book started to wane from the expectations this scenery was creating. I wasn’t expecting the book to start so slowly, given we don’t actually learn about Anna Blume, the central protagonist in the story, and the reasons for her predicament until around page 41, when she reflects back on a meeting with the editor from the newspaper her brother works for; given this book is only 188 pages long, I consider this to be a late start. While the introduction was a bit long-winded, telling, rather than showing us, how this imaginary society is, this wasn’t what bothered me about the book. I found the scope of the world Auster created to be extremely limiting.

I’m a fan of utopian and dystopian literature, so when Paul Auster’s 1987 novel In the Country of Last Things was recommended to me, I dropped what I was reading at that time and set to it immediately. I was drawn into Auster’s imagery right away from the beginning; in fact, many of his descriptive passages were quite harrowing, setting the scene of this futuristic no-named city well, but I found that the more I read, the more the book started to wane from the expectations this scenery was creating. I wasn’t expecting the book to start so slowly, given we don’t actually learn about Anna Blume, the central protagonist in the story, and the reasons for her predicament until around page 41, when she reflects back on a meeting with the editor from the newspaper her brother works for; given this book is only 188 pages long, I consider this to be a late start. While the introduction was a bit long-winded, telling, rather than showing us, how this imaginary society is, this wasn’t what bothered me about the book. I found the scope of the world Auster created to be extremely limiting.

I can’t help but call out a few of the inaccuracies in this novel. Moments that are explained to us early on turn out to be something else later in the story. For example, her brother worked for a newspaper which sent him off on assignment overseas to cover an exclusive story, but he ends up missing in the end. Having followed him to the city where our story takes place, in hopes of finding him there, Anna tells us a bit about where she is:

“this country is enormous, you understand, and there’s no telling where he might have gone. Beyond the agricultural zone to the west, there are supposedly several hundred miles of desert. Beyond that, however, one hears talk of more cities, of mountain ranges, of mines and factories, of vast territories stretching all the way to a second ocean. Perhaps there is some truth to this talk” (Auster 40).

She then goes on to tell us how she ended up in the city in the first place, having taken a lead from her brother’s employer, an editor named Bogat who “exud[es] an air of abstracted benevolence that seemed tinged with cunning, a pleasantness that masked some secret edge of cruelty” (Auster 40), a description consistent to the rest of Auster’s style. His comments, she recalls, offer some sense of foreshadow, when he states, “Don’t do it little girl… You’d be crazy to go there…. No one gets out of there. It’s the end of the goddamned world” (41). And, he was right. We never learn if she ever leaves, but this is not what bothers me so much. It’s her failed sense of geography.

I know, you’re probably thinking — what does that have to do with anything, especially in a fictional world? Yet, for all of this talk about her brother going off to a foreign land to report, and herself traveling there in hopes of finding him, you would think her knowledge of the world would be better than how she leads on. She doesn’t even know if there is a second ocean on the other side of the country she’s in — “Perhaps there is some truth to this talk,” she says. I find this to be a bit hard to believe, since it doesn’t come off as a story set in the 15th century, where cartography and exploration of the planet were still in their infancy, but rather a futuristic tale where libraries, newspapers, and even airports exist. The way I see it, she doesn’t have an excuse for not knowing.

This is but one of a couple of inconsistencies I found to be in this story of survival. Where the story lacks in plausibility, it makes up for it in Auster’s strength in characterization and imagery, though. One example of this can be found when Ferdinand dies. Anna, struggling in the streets, alone and impoverished, is offered shelter by an old, married woman, Isabel and her husband, Ferdinand, both of whom take her in for a considerable part of the story. Ferdinand proves to be an old, embittered tyrant of a husband, however, so this creates quite a bit of tension in the story. Once Ferdinand dies, we learn a lot about Isabel’s relationship to him, more so at this point than at any other when he was still alive. Auster reveals deeply embedded feelings about their life together in the simplest manner of expression:

“Isabel spent the rest of the morning fussing over Ferdinand’s body. She refused to let me help, and for several hours I just sat in my corner and watched her. It was pointless to put any clothes on Ferdinand, of course, but Isabel wouldn’t have it any other way. She wanted him to look like the man he had been years ago, before anger and self-pity had destroyed him…. Isabel worked with incredible slowness, laboring over each detail with maddening precision, never once pausing, never once speeding up, and after a while it began to get on my nerves. I wanted everything to be done with as quickly as possible, but Isabel paid no attention to me. She was so wrapped up in what she was doing, I doubt that she even knew I was there” (71).

The meticulous manner in which the matronly Isabel sets to preparing her husband for death, not a funeral per say, as dead bodies are policed up off the street like garbage and sent to the outskirts of town, but for something more than ‘processing’. Auster captures the ritual involved with preparing the dead so well in this scene that it creates a deep feeling of nostalgia and inner-peace for Isabel as one could only hope for the now widowed woman.

There are some intense moments in the story, some which left me cringing from the suspense Auster’s dramatization creates. There are also some dull points in the story, as well. While I enjoyed reading about the characters in this story, it is safe to say that I found it a bit lacking to believe in the dystopian world he creates, a world with no-name and no sense of itself. A bit disappointing really, but I won’t let this novel keep me from reading any of this other books. He has a great writer’s voice; it’s just that in the end, this fallen society leaves me wanting more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.